This blog post is the eighth chapter of a series entitled “How to Qualify for Medicaid in Pennsylvania.” This post focuses specifically on how to qualify by spending down. Qualifying for Medicaid can be confusing and complicated, but this guide helps explain it easily. You can order a copy of the complete guide here.

Many nursing home residents need to “spend down” to qualify for Medicaid because their countable assets exceed their applicable limits.

Now that you know what assets are countable, and what the limits are, you should be able to calculate how much you are over the limit. Getting qualified for Medicaid is mostly about reducing countable assets to an amount below the applicable limit.

Many people qualify by simply spending their excess assets, usually on nursing home care. But there are alternatives.

Many people qualify by simply spending their excess assets, usually on nursing home care. But there are other alternatives.

Asset Spend Down for Medicaid: Exempt Transfers

One way to get below the asset limit is to transfer excess assets in a way that will not result in the ineligibility period discussed in the chapter on gifts.

Even during the look-back period, an applicant (or a community spouse) may make penalty-free transfers of assets to:

A disabled or blind son or daughter. The son or daughter must meet the definition of “disabled” used by the federal government to award Social Security disability or SSI benefits, or meet the federal government’s definition of legal blindness.

A son or daughter under age 21.

Trust for a son or daughter who is disabled, blind, or under 21. Besides transferring assets directly to a child who meets one of these criteria, a penalty-free transfer can also be made to a trust for that child’s benefit. A trust may be more appropriate for someone who suffers from a cognitive impairment or has trouble managing money.

The community spouse. Assets may be freely transferred between spouses with no penalty. So an applicant who must spend down to $2,400 may transfer a countable asset worth $100,000 to his or her spouse.

However, this exemption gets you only so far. Remember that the community spouse has a limit (the CSRA) on countable assets.

Trust “established solely for the benefit of an individual under 65 years of age who is disabled.” This exemption specifically includes transfers to a so-called “self-settled” special needs trust that a disabled person under age 65 may create, using his or her own assets.

An applicant who resides in a nursing home because of a disabling accident or condition, and is not yet 65, can qualify easily by creating such a trust and putting excess assets into it. The trust is an exempt asset, and can pay for things to enhance the recipient’s life, such as medical equipment, therapy, private nurses or aides, entertainment, and so on.

This exemption is not limited to the applicant’s own self- settled special needs trust, however. It applies to transfers made to a trust for any disabled individual under age 65, so long as the trust is established for the disabled individual’s “sole benefit.” Under Pennsylvania Medicaid guidelines, a “sole benefit” trust has certain specific requirements, and should be drafted by a lawyer experienced in this area of the law.

Transfer Residence for Medicaid Spend Down

Some asset transfers apply only to the personal residence of the applicant (or community spouse). Title to that residence may be transferred penalty-free to:

The community spouse.

A caregiver child, that is, a son or daughter who resided in the applicant’s home for at least two years before institutionalization, and who provided care which permitted the applicant to reside at home rather than in an institution.

A son or daughter who is disabled, blind, or under 21.

Sibling with an equity interest. If the applicant’s sibling has an equity interest in the residence, and has resided there for at least one year immediately before the applicant was institutionalized, there is no penalty for deeding the applicant’s interest to that sibling.

Example: Two sisters who never married live in a house they inherited from their father, and which is titled jointly in their names. One sister moves to a nursing home and applies for Medicaid. She can deed her interest in the house to the other sister with no penalty.

Other Medicaid Spend Down Exemptions

Tax refund. You may recall from the section on Exempt (Non- Countable) Assets that a federal tax refund received by an applicant, recipient, or community spouse is not countable for 12 months after it is received. During that 12 months, a federal tax refund may be gifted away without penalty.

Other exemptions. Medicaid law contains several other transfer exemptions that are hard to define with any precision:

- Transfers as to which it can be shown that the transfer or intended to dispose of the asset at fair market value or for other valuable consideration.

- Transfers made exclusively for a purpose other than to qualify for Medicaid.

- Transfers that would result in a period of ineligibility, however the Department of Human Services determines that denial of eligibility would cause “undue hardship.”

Most of the exempt transfers allowed by Medicaid law are unambiguous. For example, if an applicant can prove that her son receives Social Security disability benefits, there will be no doubt that a transfer to that son is exempt.

But what constitutes a transfer “made exclusively for a purpose other than to qualify” for Medicaid? Suppose an applicant paid for a year of his granddaughter’s college tuition four years ago when he was healthy, employed, and age 61, but then recently suffered a sudden, massive stroke that landed him permanently in a nursing home at the relatively young age of 65.

Most of the exempt transfers allowed by Medicaid law are unambiguous.

That applicant would have a good argument that the transfer of assets to his granddaughter for tuition was made with no thought of spending down to qualify for Medicaid. An administrative law judge hearing the case may rule exactly that way.

But that doesn’t mean that paying for a grandchild’s college tuition is always an exempt transfer. A case in which an applicant paid her grandson’s college costs six months before applying for Medicaid, when she was already age 92 and living in an assisted living facility, would look much different to a caseworker or judge.

These three other exemptions have their uses, but whether or not they will be approved in any particular instance is highly dependent upon the specific facts of the case.

In the case of a transfer “made exclusively for a purpose other than to qualify” for Medicaid, the state will normally presume that a transfer during the look-back period was a gift.

However, the regulations specify some situations in which that presumption is considered to be rebutted, including transfers made as a result of a court order or written settlement of legal action, and disability or unexpected loss of assets or income after the transfer was made. This list does not preclude other circumstances in which a transfer will be found to have been made for a purpose other than to qualify for Medicaid, but items on this list have the advantage of being recognized in the regulations.

Transfers for Value

Recall from the section on “Gifts and the Look-Back Period” that the law imposes a transfer penalty only if the transfer is made for less than fair consideration.

No penalty applies to asset transfers made in return for fair market value.

That means that if you spend money, and get fair market value for what you spend, there is no penalty. (Example: Spending money from your checking account on nursing home care at the facility’s usual rate.) Likewise, if you transfer title to something you own, and receive fair market value in return, there is no penalty. (Example: You deed your house to your son and he gives you a check for its value, as shown in an independent appraisal.)

An acceptable way to spend down is to pay for goods and services that you need, or that have a legitimate purpose, such as nursing home care, legal services for Medicaid planning, the withholding of taxes, and normal household expenses.

You can also spend down by buying assets that would be exempt, such as an irrevocable burial reserve, new car, replacement furnace, and so on.

Putting It All Together

Below you can find specific case studies of what spending down can look like depending on marital status.

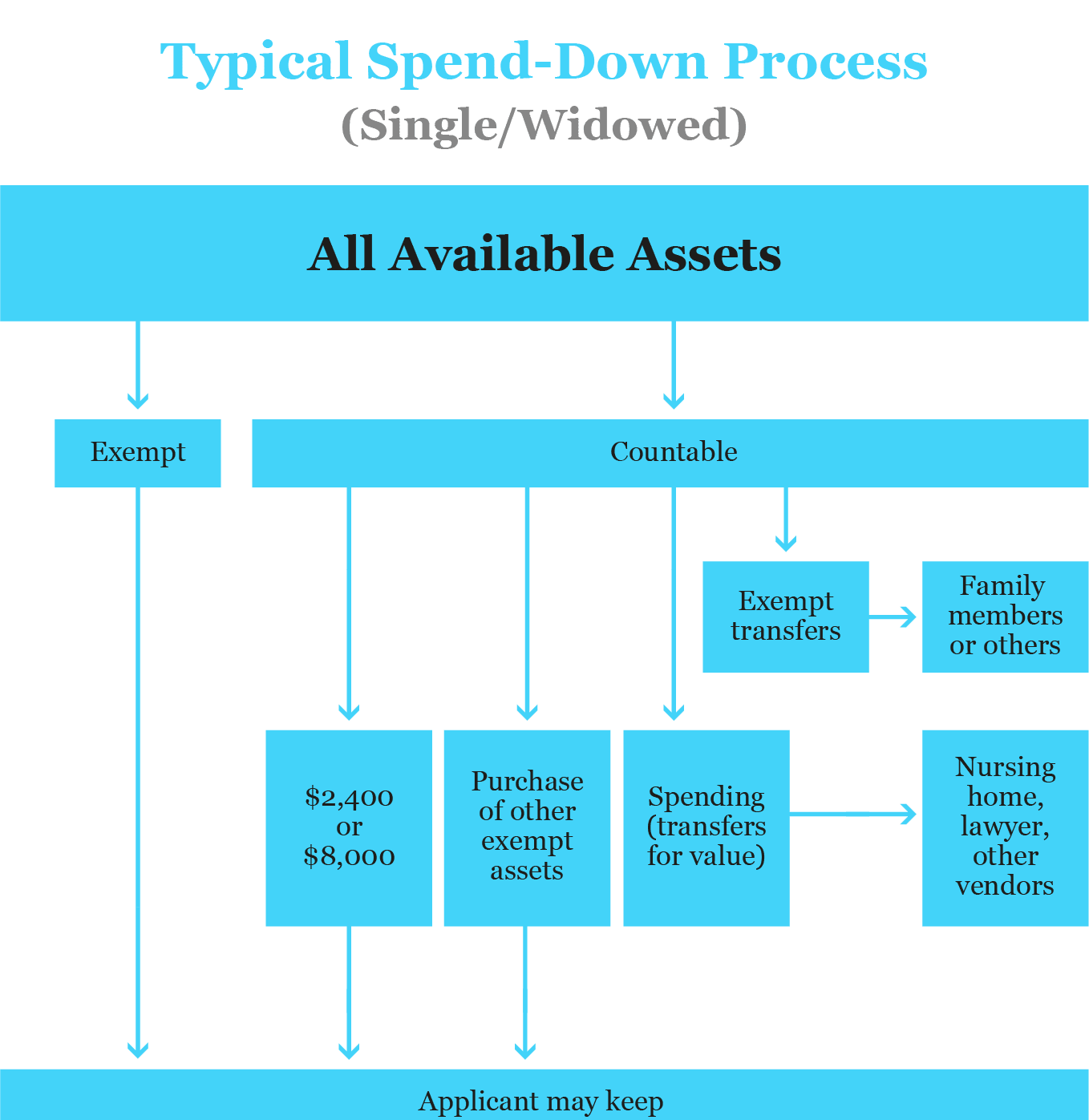

Updating the diagram developed in earlier posts, a spend- down for an applicant who is single or widowed could look like this:

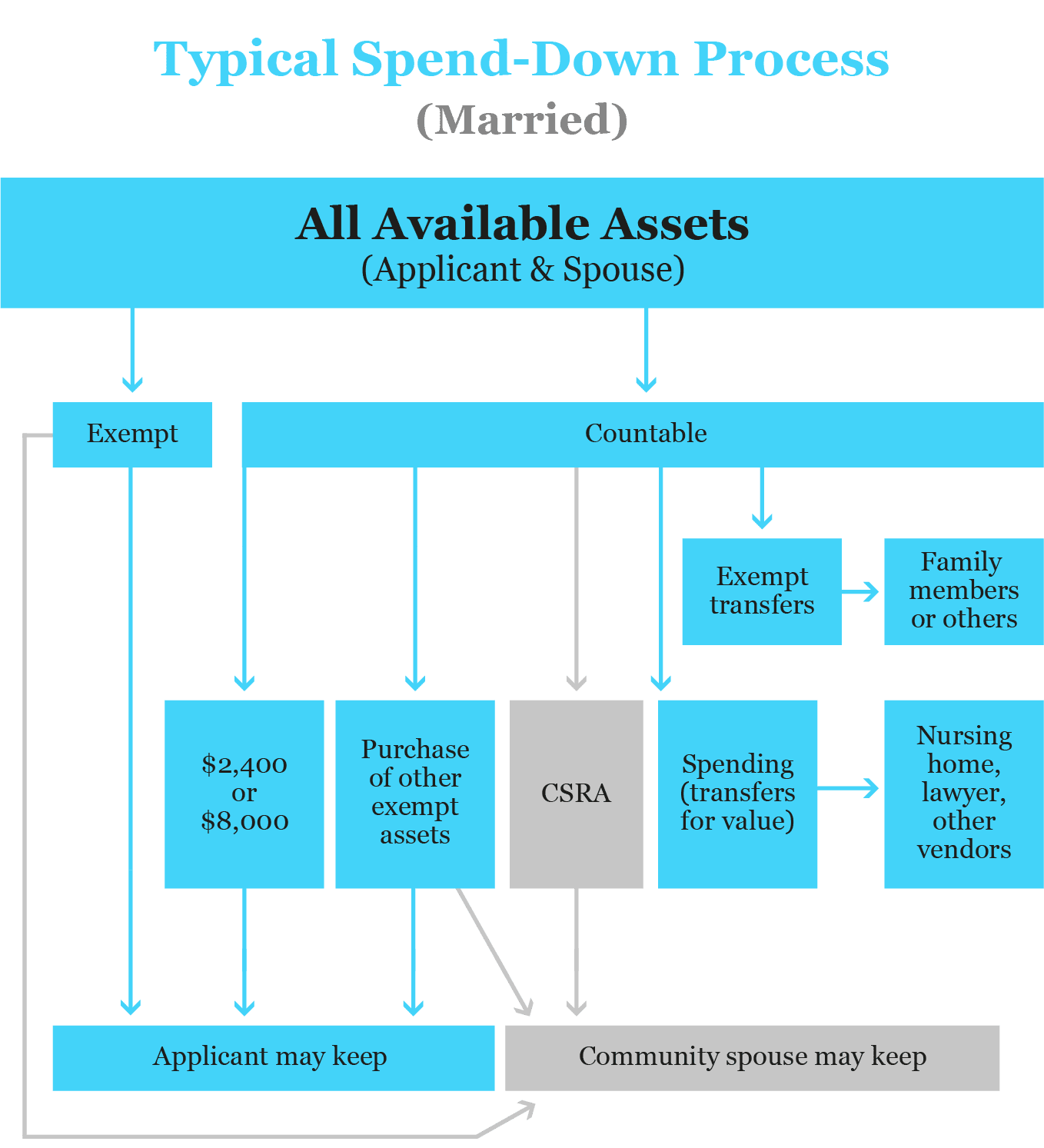

For an applicant with a community spouse, a spend-down could look like this:

CASE STUDY #1: SINGLE / WIDOWED

Jerry, a widower, has two daughters. His daughter Nora was born with Down syndrome and currently resides in a group home. His daughter Laura quit her job three years ago to move in with Jerry and care for him full-time. If not for Laura’s care, Jerry would have had to reside in a nursing facility.

Now Jerry’s immobility and dementia have both progressed to the point that Laura can no longer safely care for him at home. Laura arranges Jerry’s admission to a nursing home 10 minutes away from Jerry’s residence.

When Jerry had full mental capacity, he signed a durable power of attorney that named Laura as his agent. The POA gives Laura broad authority to act on Jerry’s behalf, including the power to make unlimited gifts to family members and create trusts.

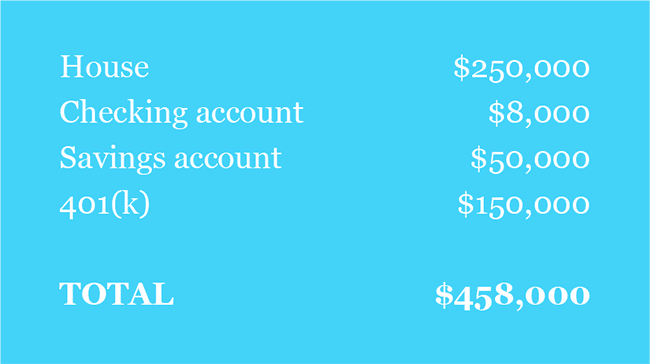

Upon admission, Jerry owns the following assets:

Jerry receives $2,150 a month from Social Security, and $950 a month from his pension.

Laura is exhausted from recent round-the-clock care that Jerry needed before his nursing home admission. After resting for a week, Laura books an appointment with an elder law attorney to see if he can help with Medicaid qualification.

The attorney reviews Jerry’s power of attorney and confirms the exact amounts of his assets and income. He gathers evidence, including a letter from Jerry’s doctor, to verify that Laura meets the definition of a caregiver child for purposes of making an exempt transfer of Jerry’s residence to Laura.

Laura gives the attorney paperwork to show that Nora receives SSI benefits, thereby confirming that Nora is disabled according to federal standards. The attorney drafts a special needs trust for the benefit of Nora.

Following the attorney’s instructions, Laura uses Jerry’s funds to buy him an irrevocable burial reserve in the maximum amount allowed in his county. She also liquidates Jerry’s 401(k), withholding 20% of its value for estimated taxes, and puts the remainder into Jerry’s checking account. Laura closes the savings account and moves its balance into checking.

It takes two months after Jerry’s nursing home admission to make all of these legal and financial arrangements. The nursing home will therefore have to be paid for Jerry’s first two months of care.

To qualify for Medicaid, Jerry’s countable assets will have to be spent down below $2,400, because his monthly income of $3,100 exceeds $2,523, the 2022 figure for determining an applicant’s asset limit.

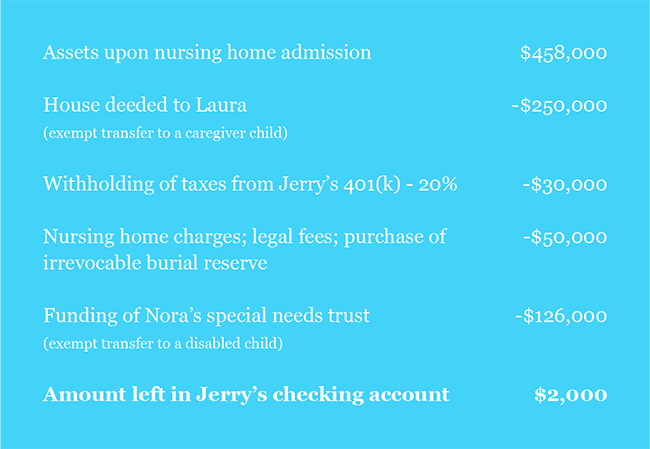

Jerry’s transfer and spend-down of assets looks like this:

Jerry now qualifies for Medicaid benefits to pay for nursing home care, where all of his physical and medical needs are met. Jerry’s income goes to the nursing home, except for a $45 monthly deduction for his personal needs and a deduction to pay his health insurance premiums.

(Note that Jerry could still have qualified if the house had been kept in his name because it is an exempt asset. But since the law permits an exempt transfer of the house to Laura, it makes sense to do that now with the rest of the Medicaid planning.)

The amount withheld from Jerry’s 401(k) is adequate to pay his taxes for the year, and he even receives a $6,000 federal tax refund. Using Jerry’s power of attorney, Laura can make an exempt transfer of the refund (within 12 months of receipt) to herself or to Nora’s trust with no penalty.

Nora’s special needs trust pays for various items that enhance her quality of life without affecting her SSI or Medicaid benefits. Laura continues to reside in Jerry’s house, returns

to work, and visits Jerry regularly. There is no penalty for transferring the house to Laura, funding Nora’s trust, or gifting away the tax refund, because they are all exempt transfers.

CASE STUDY #2: MARRIED

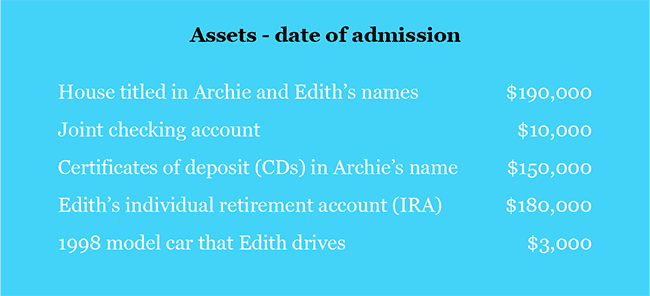

Archie, age 78, recently suffered a massive stroke. His doctor expects that Archie will need nursing home care for the rest of his life. His wife Edith, age 72, is in good health and continues to live independently in the house they formerly shared. The couple’s combined assets on the date of Archie’s nursing home admission are:

Asset spend-down and qualification

The house, car, and Edith’s IRA are all exempt assets. That leaves the checking account and CDs as the only countable assets.

Because countable assets on date of admission total $160,000, Edith is entitled to keep half – $80,000 – as her community spouse resource allowance (CSRA).

Archie’s only income is the $1,900 (gross) he receives from Social Security each month. Since that monthly amount is below $2,523, Archie’s asset limit as a Medicaid applicant will be $8,000.

Together, the couple’s combined asset limit is $88,000 ($80,000 + $8,000). Archie will therefore qualify financially for Medicaid once the combined value of their countable assets falls below $88,000.

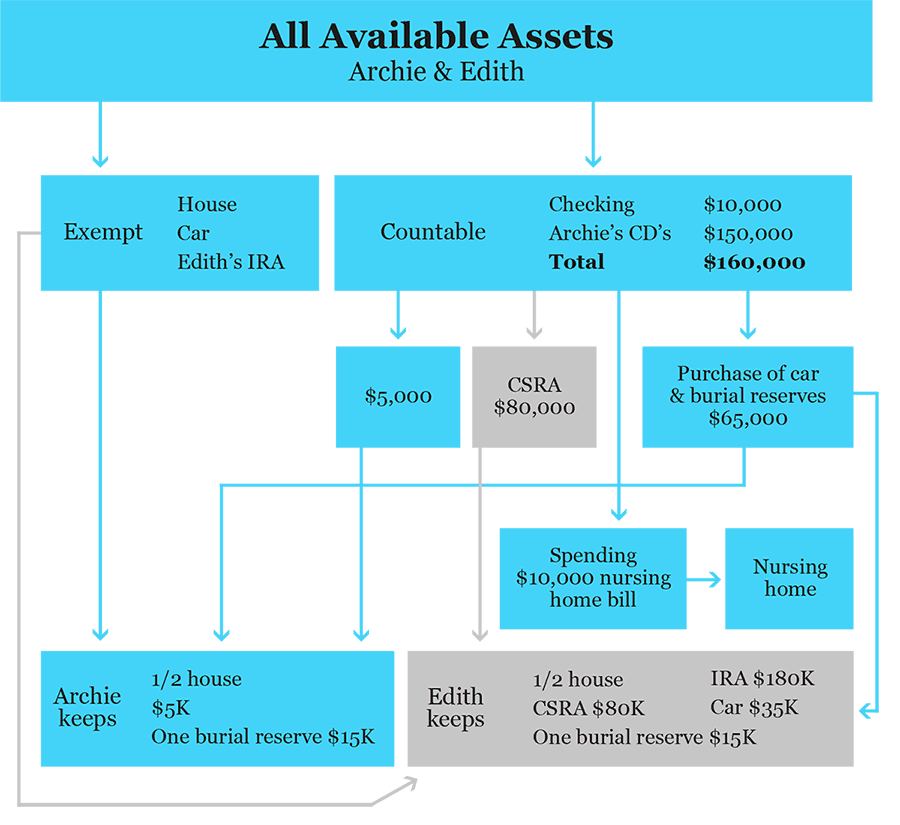

In order to spend down to qualify for benefits, Edith uses Archie’s power of attorney to liquidate $70,000 of Archie’s CDs and transfer the resulting proceeds into their joint checking account. She also re-titles the remaining $80,000 of CDs into her name. (Remember that the rules allow transfers of assets between spouses.)

In the time it takes for Edith to spend down assets, Archie incurs a nursing home bill in the amount of $10,000. Edith buys irrevocable burial reserves for each of them at $15,000 each, the maximum amount for the county in which Archie receives nursing home services. Edith buys a new car which, after trade-in of her old car, costs $35,000.

Diagramming the spend-down process looks like this:

This post is part of a series about “How to Qualify for Medicaid in Pennsylvania”

- Medicaid for Long Term Care

- Countable Assets

- Exempt (Non-Countable) Assets

- Asset Limit: Applicant & Spouse

- Spouse's Income

- When No Spend Down Is Necessary

- Gifting & the Medicaid Look Back Period

- How to "Spend Down" to Qualify

- Liability for Care Costs and Applicants' Children

- Medicaid Application Process

- What Happens After Medicaid/ Approval

- Medicaid Waiver Program

- Estate Recovery – What Happens After Death?

14. What is Medicaid Planning?